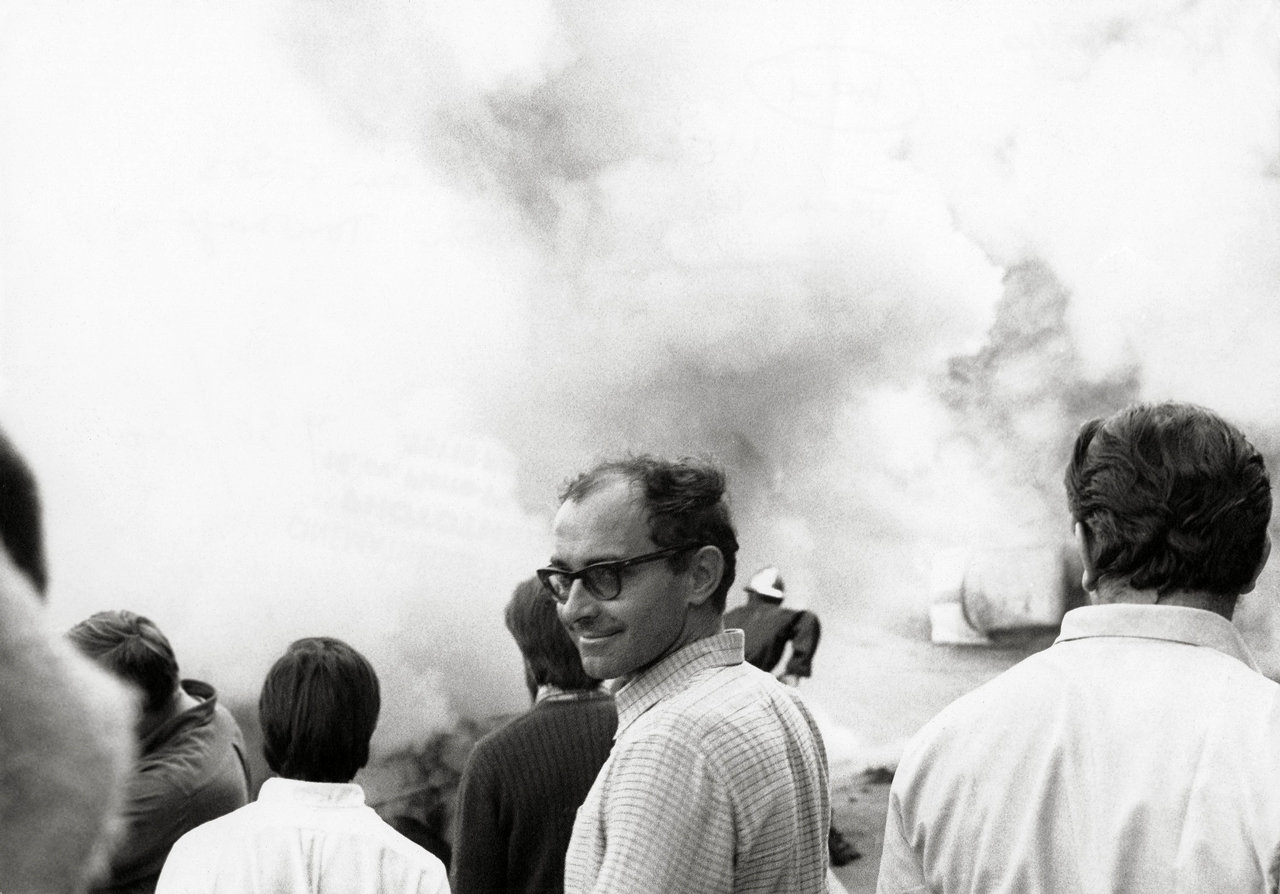

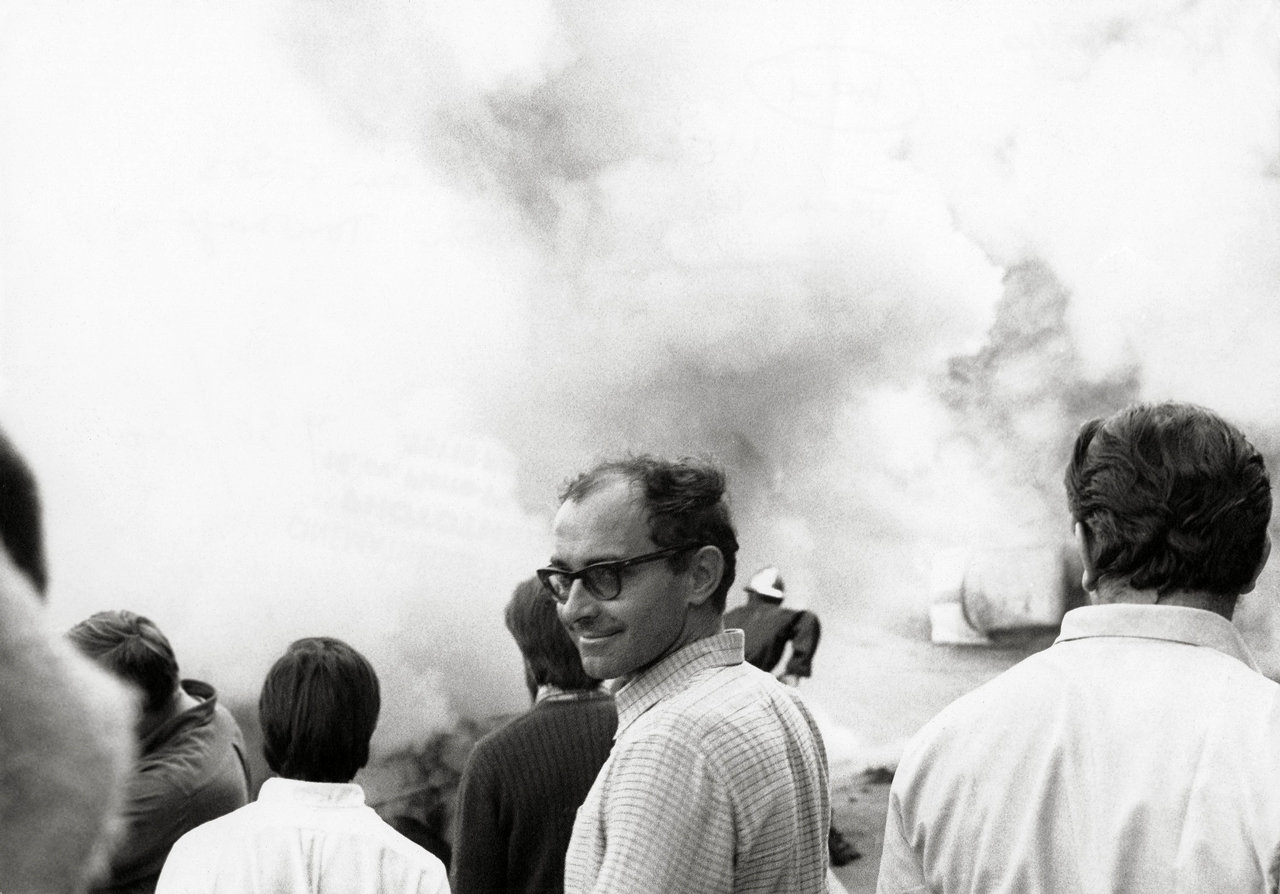

Jean-Luc Godard on the set of Weekend (1967)

“I make my films not only when I’m shooting, but as I dream, eat, read, talk to you.”

– Jean-Luc Godard

In 1967, Jean-Luc Godard supposed the end of talkie (“fin de cinema”) in the intertitles at the conclusion of his mucosa Weekend (1967), and his own work reflected this death. From the self-imposed carrion arose an versifier searching for purpose and meaning through sound and images in life, our world’s power structures, and talkie itself.

On September 13, 2022, Swiss-French filmmaker Godard passed yonder at the age of 91. Survived by his partner, filmmaker Anne-Marie Miéville, Godard leaves overdue a legacy of innovation in the seventh art and a soul of work ranging from the pop sensibilities of Breathless (1960) and Masculin féminin (1966) to the probing essay films Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998) and The Image Book (2018).

Never stagnant, Godard’s style constantly evolved and went in directions that defied dramatic conventions — satisfying an regulars was rarely, if ever, his intent. While his filmmaking career went through periods marked by particular approaches and themes, he never x-rated his roots in mucosa criticism, saying in a 1996 interview with Film Comment‘s Gavin Smith, “I don’t make a stardom between directing and criticism.”

Starting out as a mucosa critic, Godard was one of several young cinephiles (with François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Éric Rohmer, and others) who wrote for Cahiers du cinéma — the magazine which established the “auteur theory,” defining a mucosa as the megacosm of its director with nature and tendencies that can be traced throughout an unshortened filmography. Hollywood genre filmmakers like Nicholas Ray and Howard Hawks were championed by Cahiers, and their work became an important jumping-off point for the filmmaking practice of Godard and his peers.

His first short film, Une femme coquette (1955), would be followed by a few increasingly short-form dramatic experiments surpassing he received funding to produce his full-length debut, Breathless. With Breathless, the notion of a French New Wave was validated, with Truffaut’s older The 400 Blows (1959) having been a global sensation and Rivette’s debut Paris Belongs To Us (1961) in the wings.

Such work invigorated filmmakers all over the globe and codified a increasingly mainstream appreciation of cinéma vérité and low upkeep aesthetics. How many filmmakers have been inspired by the photo of Godard pushing cinematographer Raoul Coutard in a wheelchair in lieu of a camera dolly?

Jean-Luc Godard pushes cinematographer Raoul Coutard in a makeshift wheelchair dolly on the set of Breathless (1960).

More expressive well-nigh his place in mucosa history than his peers, Godard’s work referenced other films and works of art, placing himself and talkie in the lineage of art history. Like Alfred Hitchcock, a personality known within and outside of the cinema, Godard shaped himself to have a presence synonymous with film. He included his own film, Vivre sa vie (1962), at #6 in his top 10 list for Cahier‘s weightier films of 1962; “cinema” is credited as Godard’s middle name (“Jean-Luc Cinéma Godard”) in the opening titles of Band of Outsiders (1964), and in the trailer he edited for Masculin féminin his name transiently appears as “Jean-Luc God” — a ungodly stunt he would repeat then in the razzmatazz for Hélas pour moi (1993) nearly three decades later. Such provocations are commonplace in Godard’s work, and his youthful ego attracted the ire of many while still amassing imitators and disciples in mucosa studies, criticism, and filmmaking.

At the Cannes Mucosa Festival in May of 1968, Godard was among the filmmakers who tabbed for the festival to shut lanugo in solidarity with the far-left youth movement in France. “We’re talking solidarity with students and workers, and you’re talking dolly shots and close-ups,” Godard told festival attendees, adding, “You’re assholes!” However, his own work in the decade without May ’68 would largely be comprised of dolly shots and close-ups to examine political subjects with cinematic technique foregrounded. Mucosa form, or how something is represented, became the big question of his work.

A never-completed mucosa entitled Palestine Will Win, produced by Jean-Pierre Gorin and Godard’s Dziga Vertov Group, is such a work that unliable for Godard to wilt increasingly introspective as financing for his political work became difficult. When the unshortened tint of Palestine Will Win was killed by Israeli forces, Godard and Miéville took some of the surviving footage and created Ici et ailleurs (1976), a small yet seminal work in his filmography which paved the way for a new period of work that would materialize nearly a decade later.

“I never went away,” Godard said in a 1980 interview with Dick Cavett in response to his mucosa Every Man For Himself (1980) stuff described as a “comeback.” This sentiment remains true of much of the public’s sensation and understanding of his recent work, often released theatrically in major cities alone, though wangle to his work from 1980 to the present has widened considerably with home media.

Filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Nagisa Ōshima, Michael Haneke, Quentin Tarantino, and many increasingly have noted Godard’s influence on their work and on talkie as a whole. His experimentation with mucosa language has unsalaried to the way trendy films are written, shot, edited, and mixed to this day. Sounds and images as a ways of liaison are at the heart of his work, and finding new paths to convey meaning as cinematic technology wide is traceable through his oeuvre.

One of the last living filmmakers from the New Wave generation, Godard’s passing marks the latter off of a gateway to cinema’s past and a champion of cinema’s still yet-to-be-realized potential. Godard gave us glimpses into what could be, and his life’s work was the furtherance of a burgeoning medium many still take for granted. The talkie will move on without Godard, but that it can move on at all is thanks to him.

Jean-Luc Godard took this photo to signify his mucosa The Image Book (2018).

Highly prolific, Godard’s filmography can towards daunting, but here are a few works from each of his major periods that may unshut the door for remoter exploration and interest in his work and talkie as a whole:

- Breathless (1960)

- A Woman Is A Woman (1961)

- Contempt (1963)

- Pierrot le fou (1965)

- Masculin féminin (1966)

- Weekend (1967)

- British Sounds (1970)

- Tout va bien (1972)

- Ici et ailleurs (1976)

- Every Man For Himself (1980)

- Prénom Carmen (1983)

- Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998)

- For Overly Mozart (1996)

- In Praise of Love (2001)

- Notre musique (2004)

- Adieu au langage 3D (2014)